New Markets In The Arts #3: Markets as Medium

Blockchain technology has allowed us to re-imagine the arts. As a movement, it’s been rife with seemingly disparate narratives: people adopting its cocktail of hashes & cryptography as a Rorschach test for their beliefs. It’s simultaneously the most anarchist, most libertarian, most egalitarian, most socialist, most freeing, most authoritarian technology. I’ve always seen it as a tool empower creatives. That’s why I got into Bitcoin development in 2013: to help my 14-yr self get paid. As a teenager, growing up in South Africa, my games couldn’t be sold online without jumping - like a videogame character - through many hoops.

There’s a lot that has been done. There’s a lot more to explore.

In a series of posts, I will explore three broad avenues that currently interest me:

- Experimenting with Property Rights.

- Markets *as* Medium.

This is article #3: Markets *as* Medium.

Markets *as* Medium

The creative world is usually, and understandably avoidant of allowing transactions to spill into the artistic experience. Although artists need to make a living, and high flyers will buy paintings for millions of dollars, money and transactions are often described as ‘cheapening’ the experience. It can turn a complex, unquantifiable experience into a narrow one, where a number comes to dictate its meaning. It’s a strange tango, because we are wired to experience something as meaningful if it’s compared to something we understand (in this case: valuations/pricing of art). We are awed at a painting worth millions of dollars even though we might not understand the context or true meaning of it. On the other side of this dance is our desire to find experiences that aren’t just narrowed down to a price.

Thus: when we don’t have the context to understand certain art, it becomes meaningful merely because it is valued in a way we understand (this painting definitely costs more than that coffee I just bought). However, in artworks that we do understand, we see and experience complexities that if valued through a transaction becomes almost ‘dirty’.

A good example of this trade-off is research from Dan Ariely that showed us the effect of how pricing can change a complex, rewarding experience into a cheap one. When a neighbour asks your help to move a couch, we help for many reasons (and not one specific reason). It is feelings of helping another person, expectation of potential reciprocation, giving back, etc. However, when one prices this exchange (add a price to it), even though the rest of the rewards are still there, it drowns it out into only one response: what’s the value of my time and energy? If it’s low-balled, it even becomes a negative experience, where the perception changes into a belief that neighbour isn’t respecting you, or your time. “Is that what you think I’m worth?”

In a way, as an extension of this phenomenon, art becomes a language that allows us to connect to others. If we want to experience connection to the the many, to the world, we listen to pop music. If we want to experience an intimate connection to a soul that could understand more of us, we listen to an obscure genre of music. For to understand the nuances and deeper value that art at the edge of creativity allows, is to understand another person who also values that same niche.

It’s why when you find someone who enjoys the same obscure Danish electronica artist as you do, it feels more meaningful. In the same way, people lose a sense of belonging when this artist ‘blows up’, because it dilutes their intimacy to others. In that sense, there’s a resentment towards ‘commercialisation’.

Money allows us to transact with the world. But we don’t want to pay our closest friend to listen to us share our hardships.

Thus, it feels that more often than not, that art sees pricing and markets as a necessity, not necessarily as a medium. As long as it props up a $64B market, it tolerates it. Otherwise, as the art world likes to describe it, we hope to find experiences that are ‘priceless’. The hope that the experience transcends its valuation.

With that being said, in the blockchain space, we find ourselves embedded in markets. It brings about its own rule of law independent of the state’s monopoly on violence, because it makes it costly to defect from a shared narrative. Even with the advent of non-fungible tokens, collectibles and other forms of art in the blockchain space, it remains a fundamentally market-based paradigm: for good or bad. For example, those who transfer a collectible artwork on SuperRare is paying fees to a miner somewhere in the world for securing the records and provenance of this shared narrative.

Thus, when one’s canvas and paintbrushes lie amongst cryptography, markets and economics, I would hope that artists won’t ignore it. Rather: take it, and incorporate not due to necessity, but due to experimentation as a rightful medium of its own. We can explore spaces where transactions, art and connection have not tread before, and perhaps we find ourselves in uncomfortable avenues where the experience of the art ultimately feels meaningless. I, at least want to see what there is to experience. If the past two chapters of this essay series, shows, if it at minimum, it means we can create MORE art, then we pushed the boundary in the right direction.

Using markets as mediums is not new, however. There’s great examples in the past of artists playing in this space, of which I want to highlight some. This is before the blockchain era. This is not exhaustive, and if you have other favourites to share, please do.

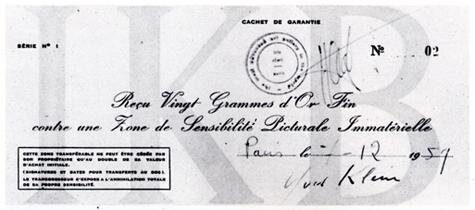

Yves Klein’s Immaterial Zones & JS Boggs “Boggs Notes”

These are fine examples where part of the transaction is part of the artwork. In the case of Klein’s work, he sold ’Immaterial Zones’ (art that doesn’t exist) for gold, whereupon the buyer would receive a receipt. If desired, the buyer could present the receipt to Klein, whereupon the receipt would be burned in a ritual that also destroyed half the gold (by throwing it into the Seine).

Thus: conceptually, the receipt of purchase is part of the artistic experience to claim the immaterial ritual.

JSG Boggs would draw a note representing the similar value of the currency he wanted to use (eg, drawing a $100 bill). If deemed acceptable, the receiver would accept it as payment and Boggs, the change and receipt. He would then sell this change and receipt to a collector, who would then be told where the transaction took place, such that collector can go and buy this fake note.

In this case, both the money AND the receipt is part of the collection and artistic experience.

Hans Haacke

Surfacing the transactions that make up the art world can reveal the hidden powers at play. 1% of artists, represent 64% of sales. It is thus not unexpected that power and connections play a role in sponsorship and curation. Hans Haacke used various artworks to display amongst other things: provenance of questionable ownership & the involvement of questionable donors (‘MoMa Poll’). Revealing this game wasn’t without protest as a few of his exhibitions were cancelled or rejected as a result. Thus, showcasing the markets behind art, it elucidates its questionable relationship to value.

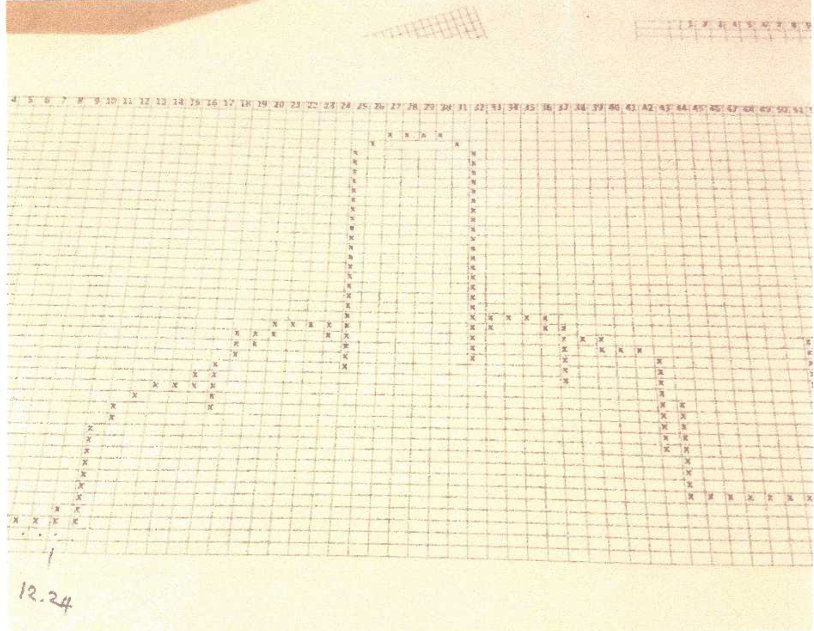

Protest TA

The lines we draw in technical analysis forms its own unique art: seeking patterns in the chaos. They have names, describing collective intuition about the nature of the participants involved.

In some cases, it has been used as protest. When Oakbay was implicated in South African state capture, James Gubb traded with himself to create a big middle finger on the stock charts. A big fuck you to the company that stole from the citizens of South Africa. He was fined for contravening regulation on trading with yourself.

Autonomous Art

Getting closer to the blockchain world, I’ve always enjoyed the bots/programs that interface with APIs. You have robots buying drugs, and artworks that continuously connect to ebay to sell itself.

Blockchain Art and Markets as Medium

There’s a lot more out there where these lines becomes blurred. In the blockchain space we’ve seen quite a handful a few of these ideas: where the market-native ideas of crypto/blockchain become part and center of the art.

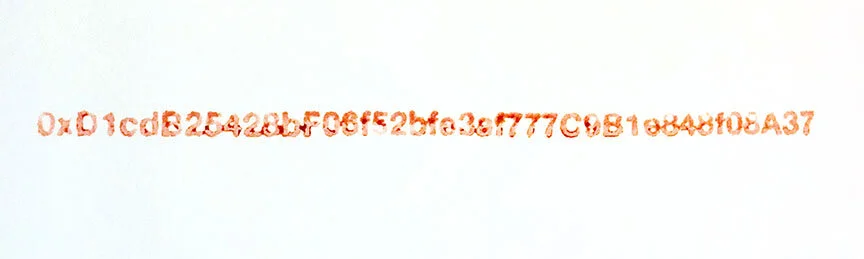

Similar in a way to Hans Haacke, Kevin Abosch highlights the relationship between art and transactions by stamping his own blood onto physical artwork that has a crypto-tradable equivalent.

DADA Channel Art was an interesting experiment first tried at the RadicalxChange conference in Detroit. Using a channel auction (rising English auction and falling Dutch auction at the same time), artists co-create a piece of work until the auction itself has completed. Thus: the artwork is created during the time of the auction. Thus: the auction itself becomes part of the experience.

In “Is This Prediction Market, Art?”, I used a prediction market to ask a set of forecasters to determine whether it, itself is art or not? If yes, it’s art. If no, it’s not art. It resolved to yes when it was done, but the outcome was disputed by the forecasters and determined as an invalid. Merely asking the question is out of bounds.

‘89 Seconds Atomized’ is a project where a film is cut into small boxes. If you own a piece, you can only view the film through that small ‘lens’ or box. The only way to view the whole film together is to collaborate with other atom holders.

Similar in a way to the artwork that sells itself on Ebay, ’Plantoid’ by Primavera de Filippi is an artwork that collects donations to pay for its reproduction.

Markets *as* Medium

In the end, new markets in the arts allow us to not just re-imagine how artists make money (new property rights), or how art is created (generative economies), but also how the markets itself act as a medium for expression. Markets themselves is an approximation of many individual self-interests, and thus it is a reflection of society. If we can utilize markets as a medium and not shy away from it, perhaps we might learn more about ourselves.

This essay series is merely a blip of what’s possible and what’s going to become possible. New markets in the arts are broad, and exciting. If you have exciting projects to share, please do.

Thank you for reading.

Thanks (we get by with a little from our friends):

This series would not exist if it wasn’t for the continuous inspiration from many individuals. Thanks to those who continue to push the envelope. This is not exhaustive and I’m sure I’m missing some people. Thanks.

María Paula Fernández, Stina Gustafsson, Fanny Lakoubay (read their amazing research on blockchain art), Billy Rennekamp, Matt Condon, Kevin Abosch, Rob Myers, Ruth Catlow, Beatriz Ramos, Judy Mam, Trent McConaghy, Greg McMullen, Dimi de Jonghe, Primavera de Filippi, Jason Bailey, Sarah Friend, Gene Kogan, Matt Hall, John Watkinson, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Brady McKenna, Jonathan Mann, Glen Weyl, Mat Dryhurst, Holly Herndon, Gabe Tumlos, & friends from Cellarius.